Supporting parents to enhance young people’s mental health

Brokering the challenge of breaking cycles of intergenerational adversity – a policy example

“Problems beget problems”,

“Like father, like son”,

“The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree”

… all statements that harness everyday communication as to how behaviours purportedly transfer from one generation to the next.

Of course, problems do not necessarily beget problems, fathers and sons are not inevitably alike, and apples can travel quite a distance from the site where they first fall. Understanding that there does not have to be an inevitability to outcomes based on previous generation specifics is core to developing policies that interrupt negative cycles of intergenerational adversity.

Two areas of significant policy relevance in the UK that have received considerable investment and that have each suffered from a failure to effectively break intergenerational cycles of adversity are mental illness and negative family relationship dynamics - specifically, family dynamics marked by poor quality parenting and inter-parental relationship discord. Historically, these areas have been treated as policy-focused silos. Yet, one likely affects the other, and without effective intervention, patterns of mental health problems and negative family interaction patterns are more likely to repeat across generations.

Mental health: the state of UK nations

Mental health disorders are the single largest cause of disability in the UK, affecting 1:4 people across their lifespan, with an estimated annual cost to the UK economy greater than £110 billion and a global cost by 2030 expected to be greater than $16 trillion.

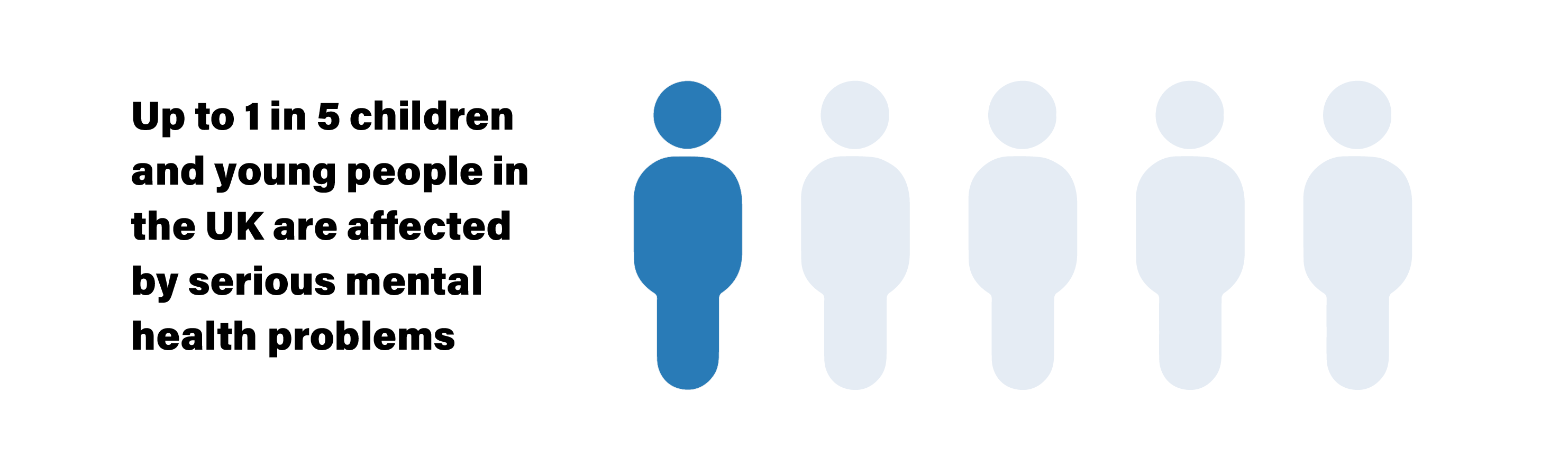

Among children and adolescents, more than 70% of serious mental health conditions, including psychiatric disorders, develop before the age of 18 years, with estimates ranging from 1:5 to 1:10 children and young people in the UK affected by serious mental health problems including anxiety, depression, conduct problems, self-harm, psychosis and suicide.

Multiple research reports suggest that mental health problems among young people are on the increase in the UK and internationally. While acknowledging difficulties in determining whether recently measured increases reflect genuinely worsening mental health or, rather, greater awareness and willingness to report such problems, it is noteworthy that there has been a threefold increase in the number of teenagers who report self-harm in England in the last decade (1:5 15 year olds). Suicide is the second leading cause of death for young people (<20 years), with the UK prevalence rates for anxiety and depression among the highest in young people aged between 5-18 years living in OECD countries.

Supporting parents to support young people's mental health

One of the most significant influences on young people’s mental health is the quality of relationships that children experience with their parents. Positive parenting has long been recognised as a core building block for children’s mental health and long-term life chances (e.g., education outcomes).

More recently, the dynamics of wider family relationships, such as the quality of the relationship between parents, has been recognised as a significant factor for children, both directly and indirectly through disruptions to the quality of relationships children experience with their parents.

Domestic adversity is often indexed by poor quality parent-child and/or inter-parental relationships and has historically served as a primary target for family-focused support and intervention policies. Decades of research has highlighted the role of parenting-focused, family-based intervention programmes and positive outcomes for children and adolescents.

More recent evidence has highlighted that where conflict and discord between parents occurs and where conflicts are frequent, intense, child related and poorly resolved, there is an increased risk of poor outcomes for children and adolescents. There is also a reduced likelihood that parenting-focused intervention programmes may lead to sustained positive or improved outcomes, including mental health outcomes.

Breaking intergenerational transmission cycles: An example of UK policy innovation

Based on an accumulation of UK and international research evidence highlighting the extensive and pervasive harm of witnessing inter-parental conflicts on child and adolescent mental health outcomes, the UK government Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) funded the Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) Programme.

The RPC programme has one core aim – to promote improved mental health outcomes for at-risk children and adolescents by reducing the damage that parental conflict causes to children. It works to achieve this aim through the provision of support to parents, training for family practitioners and better awareness, understanding and coordination of parental conflict-related services delivered by local authorities and their partners.

Its core objectives are to:

• develop an evidence base on what works to reduce parental conflict, to inform future commissioning practice; and

• help local areas integrate support to reduce parental conflict in local family services to enhance mental health and other positive outcomes for children and adolescents.

The RPC Programme has been running in England since 2018 and recently received a funding boost of £33 million in March 2022.

It recently underwent an evaluation to examine the effects of interventions on parental relationships and children’s mental health outcomes, with the evaluation report (published in August 2023). Prior to this, relatively few relationship and parenting interventions had been tested in the UK. Therefore, very little was known about the type of interventions that work to reduce parental conflict and improve the mental health and wellbeing of children in workless and disadvantaged families living in the UK.

Overall, the evaluation evidenced significant improvements in interparental relationships and child mental health for parents who completed an intervention (one of 8 possible recommended programmes).

Moving from silos to synergies: opportunity for future policy development

Contrary to the opening of this blog, “Problems do not inevitably beget problems”, particularly when robust research informs effective intervention strategies, when policy decision-making is informed accordingly and when evaluation is an integral part of this process.

Mental health problems among young people are on the rise, and rates of family conflict, discord and breakdown are also on the increase. Longitudinal evidence highlights the adverse impacts of inter-parental conflict and negative parenting experiences on children’s mental health and long-term interpersonal relationship experiences.

Supporting parents through programmes such as the RPC Programme, which is informed by an international research evidence base, offers a significant opportunity, not only to improve outcomes for children and adolescents in the long-term, but also to interrupt negative intergenerational transmission patterns, both in terms of poor mental health and negative family/interpersonal interaction patterns – the potential cost savings of which are significant.

It is time for UK policy development to move away from a siloed approach to intervention, and instead move towards a synergistic model of targeted intervention and future prevention. For example, through targeted inter-parental relationship support which reduces high levels of inter-parental conflict (intervention), this subsequently reduces the likelihood of long-term mental health problems (and disorders) developing among children and adolescents (and future adults; prevention).

A shift in high-cost late-intervention policy strategies to targeted early prevention strategies is essential if sustained progress in the reduction of intergenerational adversities is to be realised.

This blog was originally published by the Centre for Science and Policy, University of Cambridge.

It is part of a programme of work by Cambridge Public Health on the topic of ‘Breaking Intergenerational Cycles of Adversity’.