Minds and movement:

How displacement can spur intergenerational trauma

A new exhibit at the British Museum portrays how the movement of people and ideas over centuries can lead to irrevocable changes in identity and potentially contribute to intergenerational trauma. The exhibit, ‘Burma to Myanmar’, illustrates the almost innumerable cultural layers that make up the famous nation in the Far East — and how those layers have evolved over the past 1,500 years.

Dr Alexandra Green, Henry Ginsburg Curator for Southeast Asia at the British Museum, gave an invited talk on the exhibit at Cambridge, organised by the Myanmar Desk of the Refugee Hub, part of the Centre for the Study of Global Human Movement.

“Interconnected yet cut-off, rich in natural resources such as jade, rubies and teak but with much of the country living below the poverty line, Myanmar is a country that defies categorisation,” a description of the exhibit reads. Yet that defiance is linked with something complex and inherent to Burmese culture — or rather, Burmese cultures: that country, with its rich history in trade and cross-cultural connections, has hosted within its changing borders a multitude of people representing different places, norms and ideas.

Those layered identities of the Burmese peoples are, however, under existential threat from the dictatorial military regime, which seeks to erase differences between the people it rules.

In turn, that threat of erasure can damage a person’s sense of who they are — potentially eliciting not only mental distress and ill-health among individuals, families, and communities, but a cascade of intergenerational issues that may never be resolved without appropriate support.

The movement of people and ideas can stimulate adaptive growth and development. However, forced or voluntary movement in the midst of disrupted societal systems can be a traumatic experience, especially if identities, roles, bonds, and networks are broken or even eliminated.

Understanding these processes as they relate to mental health, and what can be done to attenuate adverse effects, requires an appreciation of the cultures and histories of the people involved. Green described how the multiple movements of people and ideas around the region created the unique cultural blend found in Burmese societies. The exhibit’s many objects and works of art illustrate what practices, beliefs and even materials come with people when they move.

Dr. Alexandra Green. Credit: Jonathan R. Goodman

Dr. Alexandra Green. Credit: Jonathan R. Goodman

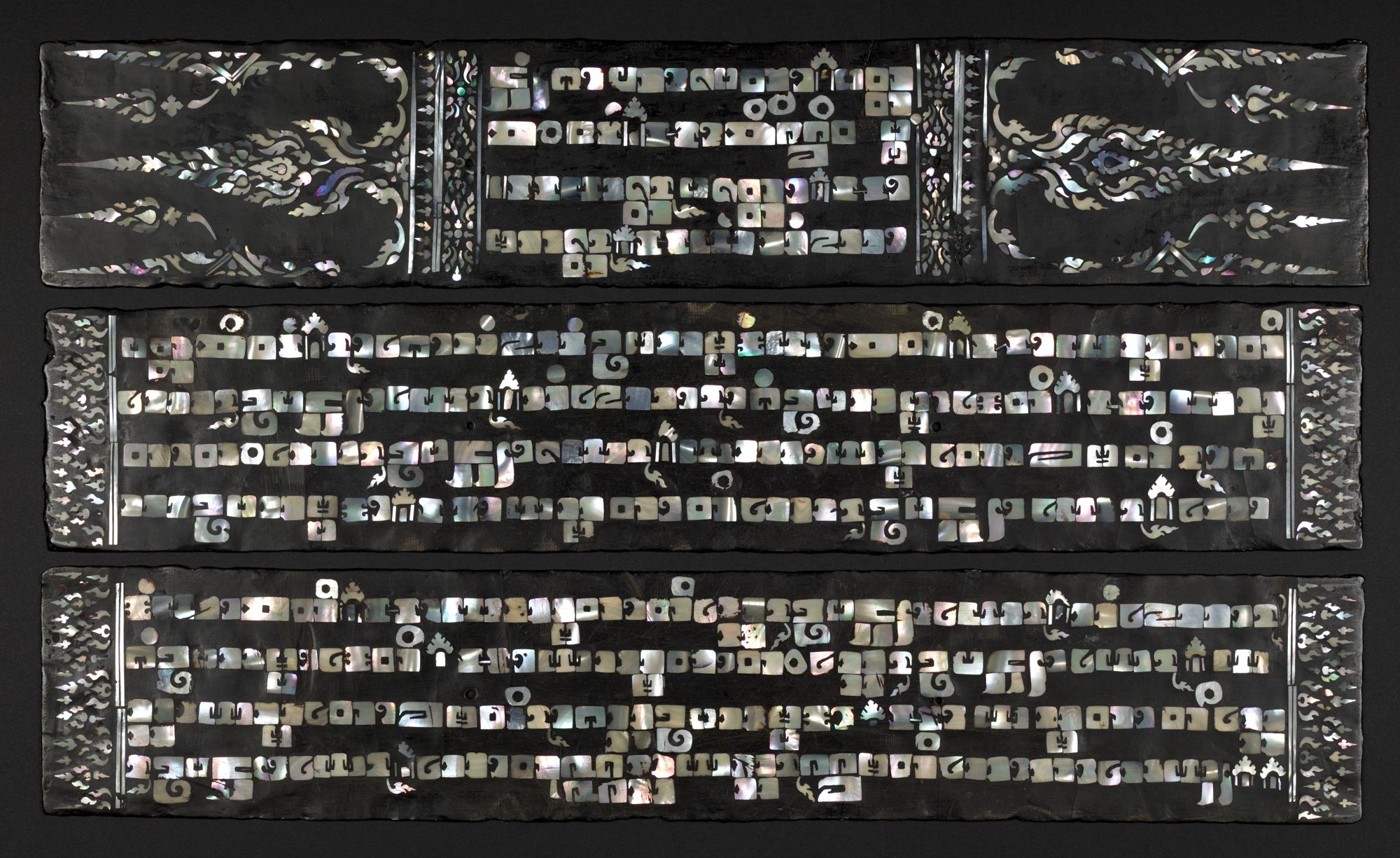

One example of this is material culture. Items like jewellery, prayer-books and clothing offer signals of shared cultural histories that we cannot infer merely from observing the behaviours of modern people.

Green mentioned one item, a Kammawasa — which are lacquer monastic texts of Buddhist scriptures produced in Burma for ordinations — from the 18th or 19th century that was crafted using mother-of-pearl lettering. This inlay technique was common in central Thailand, but not in Burma, and was a clear indication of the work of Thai artists, or their descendants, who had been relocated to central Myanmar in 1767.

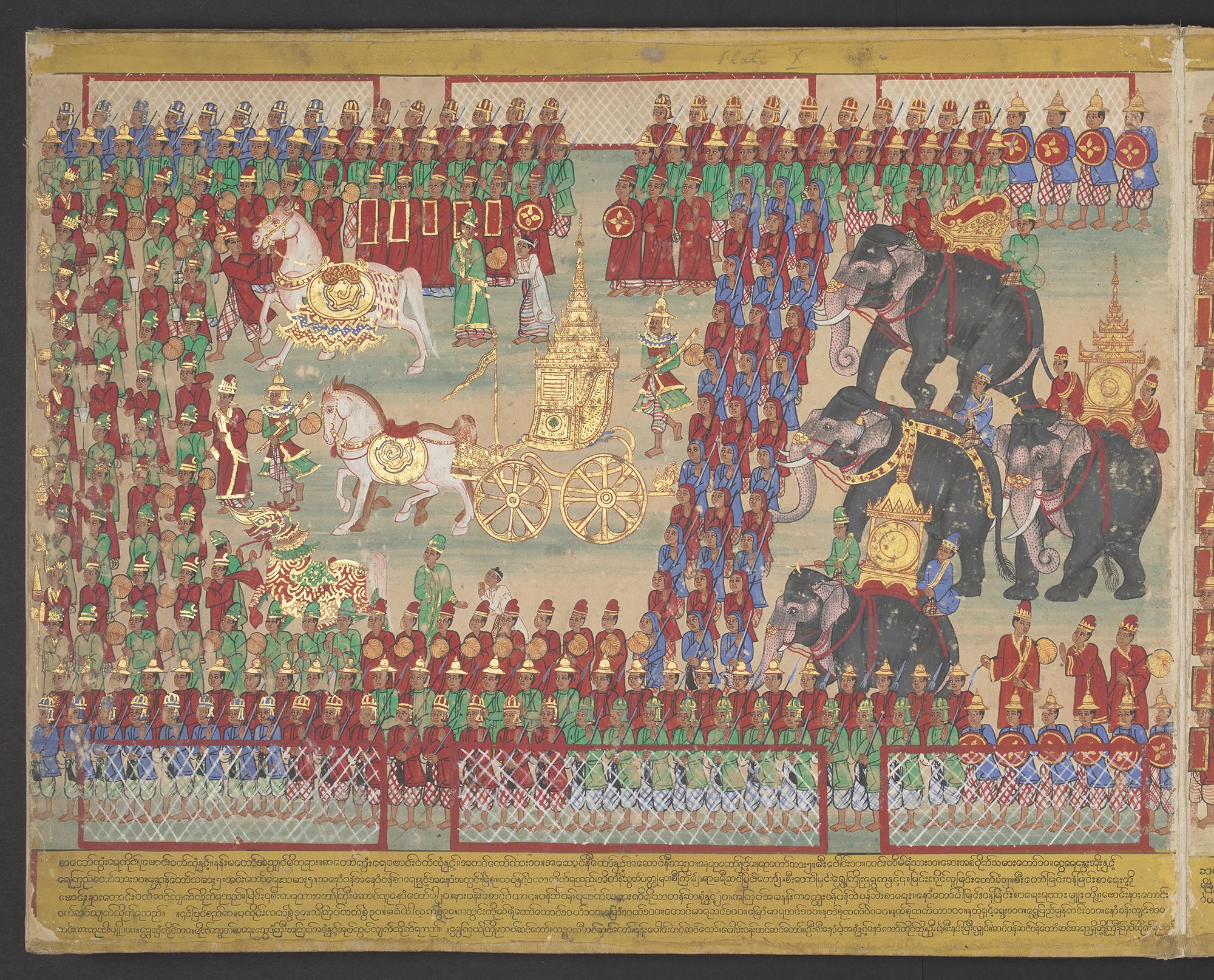

This is just one of a huge number of objects in the ‘Burma to Myanmar’ exhibition that display the complexity of Burma’s cultural history over the last millennium and a half. Conquest, in particular, effected the movement of people that brought cultural norms and practices from across Southeast Asia together. Warfare often involved taking captives — or as a description in the exhibit reads, ‘acquiring people.’

“The manuscript of the procession is in the exhibition to show how people were a major resource in Southeast Asia, and therefore warfare was not so much about territory as about control of people,” Green said. “People were relocated to work and pay taxes for different kings, rulers, chiefs.”

King Mindon’s Procession (late 19th century); British Library

King Mindon’s Procession (late 19th century); British Library

A second image — depicting the 1885 forced British exile of Mindon’s successor, Thibaw — shows another procession, but this time of the Burmese king.

Given the centrality of the monarchy to Burmese society, his ousting by the British created social upheaval — and led to a change of social norms and personal identity that lasted throughout colonial rule until 1948.

The British colonists raided Burma’s temples and often disrespected Buddhist traditions — they refused, for example, to remove their shoes in religious sites, and even used these places as military establishments.

Again, these events not only effected changes in local norms that would undoubtedly have been integral to the populace’s many ethnic identities, but blended cultural practices that, in turn, reverberated throughout the region. “With Burma’s incorporation into the British empire, it became part of the empire’s commercial networks,” Green said. “Its markets expanded to include many imported goods, and advertising developed to ensure people knew about them.”

...these events not only effected changes in local norms that would undoubtedly have been integral to the populace’s many ethnic identities, but blended cultural practices that, in turn, reverberated throughout the region.

The effects of this colonisation, however, are still felt by the populace today. While, as Green noted to us, it is obviously not possible to investigate the consequences for social identity and mental health of people conquered by Burmese rulers in the 18th century, social artifacts of British rule remain.

Poster for Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company (1930s; private collection)

Poster for Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company (1930s; private collection)

A modern crisis

Dr. Maha Y. See, who founded and directs the Myanmar Clinical Psychology Consortium (MCPC), said in an interview that class — a cultural phenomenon upheld and weaponised by British colonial rule — remains a driver of identity among Burmese people today. Moreover, the disruptions within Myanmar, such as the 2021 military coup by the Junta, can cause changes in a person’s class overnight. In other words: class is today a medium through which someone’s social identity can be altered or erased. It is weaponised by the ruling Junta much as it was by the British in the past, See said. The layers of that possibility are embedded in the country’s complex history; the consequences reverberate through generations.

Today, we can and do understand the many mental health problems that stem from forced movement and the resulting changes in a person’s or group’s identity. Addressing that growing crisis among the Burmese people, however, is a difficult — even almost impossible — problem for several reasons. The central one is the ruling Junta dictatorship, which led a coup ousting Myanmar’s democratically elected leaders in 2021.

“When one works with clients who have experienced political violence, the safety of both clients and counsellors are at risk,” See said. “Because of COVID-19 and the prevalence of mobile phone use, online counselling has become the de facto, still accessible, and relatively safe mode — and sometimes the only way — to address mental distress and ill-health in Myanmar, especially among those outside of major cities.

“In-person counselling is still preferred but increasingly impossible for an overwhelming majority because of safety, travel, scheduling and overall cost. Online counselling has allowed the MCPC alumni team to serve across national boundaries: we now work from and in Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Australia, the US and the UK for Burmese and other ethnic language–speaking clients.”

The emergence of intergenerational trauma

“Safety and security, identities and roles, (in)justice, bonds and networks, existential meaning – these are all integral to mental health, resilience, and wellbeing”, noted Dr. Eolene Boyd-MacMillan in an interview, “and are often undermined or destroyed during societal disruptions”. Depending on their starting place, people can adjust and adapt for a while. But ongoing societal disruptions can lead to mental distress, ill-health, and for some, trauma, or other diagnoses. Over time, intergenerational trauma will emerge. With appropriate support, people can process trauma and avoid passing it on to the next generation; without support, people may find it increasingly difficult to function in many areas of their lives.

Dr. Boyd-MacMillan, is a Senior Research Associate, Co-Director of IC Research, and Co-Founder of the IC-ADAPT Consortium at Cambridge’s Department of Psychiatry; she is also a member of the interdisciplinary research centre, Cambridge Public Health, and Convenor of the Myanmar Desk in the Refugee Hub, Cambridge Centre for the Study of Global Human Movement, that hosted Green’s talk about the ‘Burma to Myanmar’ exhibit.

The current situation with the Junta in Myanmar has exacerbated the problems inherent to an already poorly functioning mental health service and, for now, precludes efforts to address these problems. While emergency medical and mental health services remain available, there is no operating infrastructure for people needing mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) over an extended period and no long-term capacity building. Very few community-level experts are qualified to provide MHPSS across Myanmar. A number of people have gone through short trainings offered by non-government organisations (NGOs), but there is huge variability in training quality, supervision, and ongoing monitoring and evaluation processes, and many, many more continue to fear the stigma associated with mental health problems. “Without culturally sensitive MHPSS support, many struggle on with declining health,” Boyd-MacMillan said.

Furthermore, there are more than one hundred languages spoken in Myanmar, representing as many ethno-linguistic groups, though the majority of the population speak Burmese, whether as first or second languages. There is not, however, a sufficient effort from groups providing mental health interventions to reach those who do not primarily speak Burmese. “When researchers conduct surveys, for example, they may provide the survey questions in Burmese and in a target ethnic language,” See said. “In my team's experience, the overwhelming majority, I would estimate as many as 98% of youth participants, elect to take the survey in Burmese language.

“Because of the military's ‘Burmanisation’ programs across generations, most people cannot read or write well in their own ethnic language. We notice this also in our mental health outreach and education.”

“As part of our political stance, we provide the materials in ethnic languages,” he added. “However, most cannot read, especially in rural areas. So, face-to-face in-person or online verbal outreach in target ethnic languages are more effective and make sense.”

This problem, coupled with the short-term approaches taken by many NGOs and the general stigma against mental health interventions among many people living in or displaced from Myanmar, creates nearly impossible conditions for addressing and preventing intergenerational trauma. Training sessions for ‘psychological first aid’ workers or for counsellors can last only a few days or a few weeks — often delivered by people who only recently completed their own training. Usually on very short-term contracts, many leave the NGOs involved in these training sessions, preventing the accumulation of experiences and expertise. According to See, as few as one or two people can be responsible for mental health interventions in an entire region (e.g., during COVID, only two psychiatrists served all of Myitkyina, capital of the Kachin State, population c.150,000). While the need is great, and any psychosocial support might seem better than nothing, short-term planning and investment raises ethical as well as quality assurance questions.

Photo by Ajay Karpur on Unsplash

Photo by Ajay Karpur on Unsplash

Charlie Artingstoll, who is a Partner of the Myanmar Desk, as is See, became disillusioned while collaborating with NGOs during his initial work in the country a decade ago. After working with the United Nations and then an NGO, Artingstoll became involved with hip hop shows in Myanmar that promoted social issues. While living there prior to the 2021 coup, he became immersed in Burmese culture — and seeing the horrors that were unfolding, realised there was a need for mental health support. Eventually, Artingstoll started Sin Sin Bar, a communications organisation dedicated to social change. Working in tandem with See and MCPC, Artingstoll created mental health outreach and education content for social media that was promoted by influencers across Myanmar.

MCPC have organised other community outreach programmes — with the aim of making mental health not only an acceptable topic but of creating a future possibility where clinical and counselling psychology education are taken seriously as part of a broader long-term vision for public mental health in Myanmar. “Right now, it’s like having a hospital full of people with only first aid training,” Artingstoll said. While psychiatric support exists and medications are prescribed, both See and Artingstoll said effective mental health and psychosocial interventions exist only when the mental health workers are well-trained and supervised, and where referral resources are available for those who need more help.

For now, See and his MCPC team work primarily with displaced people living outside Myanmar and who have internet access. People, for example, who were members of powerful political families prior to the coup who are now tilling fields for their livelihood require a huge amount of support to confront the realities of what has happened. The effects of physical torture also have a dramatic impact on a person’s psychological well-being — and with millions of displaced people living across Southeast Asia, a serious, long-term approach for public mental health training, education and service provision is essential.

A broader problem

While millions of people are living displaced within and outside Myanmar, many millions more have left their homes — often, not by choice — worldwide. According to the United Nations, the largest displaced population worldwide is from Syria. Moreover, and despite impressions in the Western world otherwise, 76% of these refugees are hosted in low- and middle-income countries, such as Lebanon and Jordan. Displaced women, in particular, face a host of psychosocial issues, including rape, forced impregnation, sexual trafficking, and slavery, according to Luma Bashmi, a PhD candidate at King’s College, Cambridge, who is also a Lecturer in Psychology at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland - Bahrain (RCSI).

For her PhD, Bashmi is exploring how a mental health intervention checklist may be successfully implemented among refugees in Lebanon and Jordan. “Many refugees lose their personal and national identities, as well as their community identities,” Bashmi said in an interview. “Someone escaping their country is leaving somewhere dangerous, looking towards a safer place. Yet people from Syria, for example, often don’t have the paperwork that allows them to leave and find opportunities.”

Physical danger, cultural tensions between refugee and host populations, and lack of opportunity are three things that can — quite obviously — contribute to the development of mental health problems among displaced populations, with potential intergenerational effects. Parents forced to move to new places who cannot find work and feel isolated also feel less safe and secure and are less likely to be able to care adequately for their children, for example.

Bashmi’s work in part focuses on engaging with Arabic-speaking refugee communities to assess their readiness, and what they think is needed, for a co-developed mental health intervention. When people arrive to host countries with ‘refugee status’, they often face discrimination and hostility, undermining a sense of belonging and reducing employment opportunities. In extreme scenarios, tensions may arise between refugees and host communities, where refugees are perceived as outsiders and posing a threat to locals’ safety and livelihoods, which leads to increased risk of conflict. Psychosocial interventions within a public mental health framework that aim at increasing tolerance and social understanding amongst refugee and host communities can not only help to improve social dynamics, but strengthen mental health, resilience and wellbeing across all communities.

“My ultimate goal for this research is to develop a MHPSS framework to guide practitioners on the essential components needed when designing and implementing interventions targeting non-clinical populations in crisis or post-conflict settings,” Bashmi said. “While reviewing the literature, an overarching model I’m considering is called ‘IC-ADAPT’, which integrates two models, ‘integrative complexity’ (IC) — focusing on the interactions among people and their environments while working across difference and disagreement yet holding on to core values— and ADAPT – designed with and for those suffering from the effects of persecution and traumatic experiences as a consequence of societal disruptions.”

With humanitarian crises unfolding across the world — for example, nearly two million people in Gaza are being displaced as a result of the ongoing conflict in the Middle East — the need for mental health interventions among refugees will only grow. And for each population, whether Burmese, Syrian, Gazan, Ukrainian, or any other, culturally appropriate mental health and psychosocial support that recognises the impact of societal disruptions across the generations and enables people to work together across difference and disagreement is essential. No one tool or intervention will work across the world. Culturally sensitive, community-level training and monitored service provision, like that offered by the MCPC team, is essential. This involves not only a local understanding of people and culture but of the shared histories that led to the crisis, whatever it is, resulting in displacement. Being a refugee represents much more than leaving your home: it is the confluence of history, culture, and struggle that results in a need for escape.

The mental health of these groups is, moreover, an essential part of their well-being. “Mental health is crucial for the whole hierarchy of needs,” Bashmi said. People who are suffering from mental ill health may struggle to find work or shelter for themselves and loved ones — and recent research from Cambridge and Anglia Ruskin University shows that people with severe mental health problems are nearly twice as likely to develop physical co-morbidities, including diseases like cancer.

Given that both socioeconomic factors, such as war and poverty, as well as climate change are increasing the numbers of displaced people and refugees worldwide, developing culturally sensitive public mental health services and interventions as part of sustainable long-term efforts to increase local capacity and infrastructure is increasingly crucial. Researchers at Cambridge Public Health and beyond aim to play a part in finding and implementing those interventions — though to the degree that this problem is dismissed and only short-term interventions are used without long-term structural planning and investment, the cycle of intergenerational adversity will continue.

Photo by AHMAD BADER on Unsplash

Photo by AHMAD BADER on Unsplash

Further resources

- 'Burma to Myanmar' Exhibit: British Museum

- Cambridge refugee hub

- Myanmar Clinical Psychology Consortium

- Mental Health Resource Directory in 17 languages used in Myanmar

- 2022 case study: mental health project conducted in Myanmar

- Cambridge Public Health Spotlight on: Charlie Artingstoll

- Geopolitics and genocide: The Gambia vs. Myanmar at the International Court of Justice

- Staying put in an era of climate change: The geographies, legalities, and public health implications of immobility

- U-Thant House

- Lost Footsteps

- Embrace Lebanon mental health service

- Lebanon's national mental health programme

- Mental health resources in Arabic

- IC-ADAPT Consortium

- Healthcare in Conflict research network

- Silk Roads Programme

- Cambridge-UNICEF partnership supporting children in the Rohingya refugee camps of Bangladesh